Being an artist, people tend to think of me as a person that happens to make art. But there’s another kind of reality to it—everything I do is art. An artist creates a persona. One of the best examples is Andy Warhol. Everything he did was art and it all fit together—if you asked him a question he never had much of an answer, he was always flat, totally deadpan. Likewise, his work was always flat and literal. He didn't invent imagery as much as he absorbed it. I’m kind of like that too. I’m not like Andy Warhol, but I do have this persona that is not about me as a person. It’s about the artist in my studio. That artist has a belief that he never needs to leave his studio for anything—that everything he needs is in this workspace. I can make my own cell phone, my own brain, my own x-ray images, my own tribal icons, my own chair. I never need to leave to get something because I can make it in house.

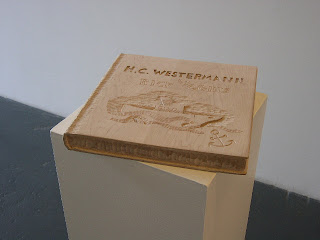

A few examples you might look at; I wrote a book on one of my heroes, H.C. Westerman, and you can see that with my tools, and skills, I’m able to write a scholarly book.

I made “The Heart Lung Machine.” It’s inspired by my interest in medical science, especially organ transplant. One of the most difficult challenges of heart transplant was to invent a machine that can take the place, temporarily, of the heart and lungs. It took years for scientists to perfect that machine. It only took a few weeks for me to make a heart lung machine.

Right now I’m working on a cyclotron, a particle accelerator which speeds up atomic matter to a high velocity, creating high energy. It makes atoms run into each other so they produce a collision that is similar to the big bang. It takes billions of dollars to make one of these things, but I can make it right here in my studio, no problem. Check in later this year, and I’ll have finished my own cyclotron that collides particles, enabling us to see the very creation of the universe.

In the studio I can explore anything—global warming, the earth as viewed from space, human evolution, the destruction of the World Trade Center, and much more. It’s an idea of a persona and workplace where nothing is too small, too big, too complicated, or too theoretical to be put together and taken apart.